This website contains some of the completed units of my HNC level 4 qualification in Health and Social Care. Some of the units within this website are a level 5 and many of the questions and answers will also be relevant to QCF qualifications or ATHE Level 4 Extended Diploma in Management for Health and Social Care and to the first 2 years of a BA or BSc in Health and Social Care.

THIS WORK IS ORIGINAL UNLESS OTHERWISE CITED. PLEASE USE GOOD REFERENCING ETIQUETTE – IF YOU USE THIS BLOG TO SUPPORT YOUR OWN WORK PLEASE CITE IT! 🙂 S.D

A little bit about myself first. I am a 40 something mum, student and big fan of coffee. I also work for a national learning disability charity as a support worker, and have worked within health and social care for the past 7 years. I continually juggle all 3 of aspects, as I’m certain many other working student parents do. The aim of this blog is to add an individual and personal touch to one of the “partnership” units for the HNC Health and Social Care level 4 course I am studying, and of course to allow me to present my knowledge in a different way, rather than just on paper. Whilst not completely informal, this blog will be less academic than a written essay as a way of appealing to readers. This work is original, and any sources I have used are referenced.

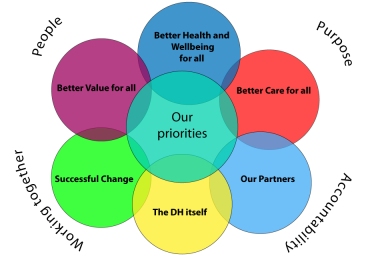

Promoting Positive Partnership Working

The term “Partnership” is somewhat of a buzz word within the remit of health and social care currently. This well overdue way of working has only in recent years been highlighted as a crucial expectation in the support of individuals. Can everybody within a partnership still work in a way which permits their own expertise and unique identity to be recognised? I think the answer is yes….. If it’s done successfully.

To get a better understanding of the various types of partnership models, in the following entries I am going to look at some aspects of their function, and analyse how they impact on partnership working. I will also be looking at the various types of legislation and policies which support collaborative working, and debating the effect that conflict between practice and policy has on the partnership.

Working in partnership to support people is considered to be the “gold standard” in terms of providing a better delivery of care. However this can only be achieved if each stakeholder in the collaboration is working to their full potential. To better understand how things can go wrong we need to be aware of the many factors which can influence the outcome of teamwork. There are no shortage of examples – we see and hear about poor care in the news and in the media all the time. What is most evident in accounts where care has not been provided well is that there has been a failure to communicate effectively. Illustrated below are some examples of how this may occur , but this list is by no means exhaustive.

- Conflicting personalities within the team.

- The Duplication of tasks.

- Lack of accountability from professionals.

- The individual has many complex issues which have not been clearly defined.

- Prejudice or discrimination from members of the team.

- Members of the partnership have different perspectives on how outcomes should be achieved.

- Poor understanding of job responsibilities

- Lack of information sharing.

- Weak negotiation skills.

Helen Dickinson and Jon Glasby wrote a 2008 article titled “Partnership working: evaluation” which, other than providing interesting reading material, stated the following:

“Despite international interest in partnership it has not been demonstrated that this way of working necessarily improves outcomes for service users. This might be considered problematic in itself (given that partnerships have assumed a central role in many areas of public policy). Partnerships are difficult to evaluate effectively and evaluations involve a series of trade-offs regarding what sort of coverage is gained, whose perspectives to involve and the main focus of the study. Not every evaluation will be able to cover every possibility ” (Glasby, 2016).

This does not suggest that partnership isn’t beneficial for individuals, but it does highlight the lack of an evaluation process which would identify if outcomes were improved or not. This appears to be occurring because assessing the team relationship is an extremely complex and fragmented task, which possibly would involve getting the opinion of all members of the team, and also maintaining an unbiased viewpoint.

Models of Partnership Working

Partnership working is mentioned in almost every policy and piece of legislation surrounding health and social care. The “Valuing People Now” white paper promotes collaborative working alongside people with learning disabilities by stating:

“Our Vision can only be delivered through a partnership approach”

and

“Professional structures need to ensure that people with learning disabilities and their families have easy access to services from all agencies. To achieve this, Partnership Boards should review the role and function of community learning disability teams in order to ensure that:

● All professional staff become accountable for the outcome of their work to the local partnership arrangements – whilst ensuring the retention of appropriate professional accountabilities and support;

● All professional staff become a resource for the local implementation of the White Paper and to help achieve social inclusion for people with learning disabilities;

● Organisational structures encourage and promote inclusive working with staff from the fields of housing, education, primary care, employment and leisure”.

The newer models of collaborative work appear to have a more succinct definition with clearer guidelines and expectations. Collaborations can be broken down into various sub-types – Hybrid, Coalition, Coordinated and Unified. A hybrid or blended model of partnership is defined as a mix of public and private stakeholders and is an organisational form which challenges the polarity between sectors.

The Hybrid Model

Hybrid organisations are seen as blurring the boundaries among the private, public and third sectors; they are businesses with primarily social objectives whose surpluses are reinvested to address a social or environmental need (Kelly Hall, 2015).

An example of this hybridity could be an individual who, due to changes in the law or out of personal choice receives some of their care package funded via the county council, and pays a personal contribution to cover the outstanding cost of their support or care. We also see examples of hybrid partnership within the health care system , with people choosing to receive some of their treatment free under the NHS, but also having the option to pay and get faster care privately. In local councils the hybrid model is becoming increasingly familiar as social services departments do not have access to unlimited funding, and are unable to keep up with the ever-rising costs and demands placed upon them.

Looking at the privately funded aspect of the hybrid model clearly shows that there are benefits and drawbacks which are dependent upon the financial status of the individual. Factsheet 6 from The Care Bill which is due to be published in 2017 aims to cap care costs at £72,000. The Bill gives clear descriptors of who is responsible for what and states that:

individuals are responsible for:

- Any extra care costs, for example if they choose a more expensive care option

- Support not covered in the care and support package (gardeners, cleaners)

- a contribution to general living costs if they are in a care home, if they can afford it. General living costs reflect the costs that people would have to meet if they were living in their own home – such as for food, energy bills and accommodation. People will be expected to pay around £12,000 a year towards their general living costs if they can afford it (Department of Health, 2013).

The Government is responsible for:

- Any further reasonable care costs once an individual reaches the £72,000 cap

- Financial help to people with their care and/or general living costs, if they have less than around £17,000 in assets, and if they do not have enough income to cover their care costs

What constitutes a more expensive care option – better quality of care? The choice between having a clean and dirty home? The Care Bill goes on to say:

“The combined effect of the cap and a higher means test threshold will see more people receive public funding.” (Department of Health, 2013)

While the cap is certainly good news for those whose savings are being eaten away by the increasing cost of social care, it may mean that individuals still have to “settle” for a care package that just meets the very edges of their needs and keeps them afloat, but in a state of relative poverty at the same time. Private care could also result in having to sell the house of the individual to fund the current living arrangements which is an additional stress factor for families.

There are of course huge benefits to being able to choose a private care provider. The individual is able to exercise their autonomy and choose a setting which they feel is perfectly suited to them. There is less likely to be dissatisfaction if provision has been chosen by the individual and often a faster and more convenient transfer process. Within the hybrid model, choosing to access private provision is not considered switching sectors but rather an integration with other stakeholders based on rights, choice and independence. It demonstrates shared power, effective sharing of information and examination of all client pathways. Hybridity appears to promote autonomy in an extremely honest and transparent way by:

- supporting in making clear well informed decisions, even if it is not in a particular stakeholders best financial interest

- promoting part-private care if that is what the individual has chosen

- being able to sign-post to or provide financial advice

- Remaining focused on the independent choice of the individual

What is a Coordinated Model?

“Services work together in a planned and systematic manner towards shared and agreed goals” (Rose, 2007)”.

“Individuals remain in separate organisations and locations but develop formal ways of working across boundaries” (Leathard, 2011).

There is no one clear cut definition of Coordinated models of partnership working, but rather broader terms which point to each agency assessing the individual on their own terms with the result being joined-up strategies and multidisciplinary team led across all levels from front line support organisations to local authority assessment.

- Coordinated working: Professionals from different agencies assess separately the needs of the individual, but meet together to discuss their findings and set goals. The focus of service delivery will be multi-agency and coordination of services across agencies is achieved by a multi-agency panel or task group. Funding may be single or multi-agency (Mary Atkinson, 2007).

- There is no one model of care co-ordination, but evidence suggests that joint commissioning between health and social care that results in a multi-component approach is likely to achieve better results than those that rely on a single or limited set of strategies (Ham, Davies and Kodner, 2016)

- care coordination , a service or scheme involving two or more agencies that provide individuals and their families with a system whereby services from different agencies are coordinated. Care coordination encompasses individual tailoring of services based on assessment of need, inter-agency collaboration at strategic and practice levels” (University of york, 2005).

One interesting aspect of this model is the group dynamic. A good outcome for the individual is almost entirely dependent upon good communication taking place. This becomes more complex within a partnership as each stakeholder is required to convey their own strategy, and take into account those of the other team members. The Codes of Practice for Social Care Workers advise that members of a partnership should recognise and respect the roles of other agencies working alongside them and that communication should be open, appropriate, accurate and straightforward (General Social Care Council, 2010). This equates to good relationships and effective communication.

Tuckman (1965), is best known for work in the field of psychology and brought us his study titled “Developmental Sequence in Small Groups” which demonstrated a model in which groups experience 4-5 stages of dynamics.

A Good relationship, especially within a coordinated partnership where each member has their own agenda to discuss, is dependent upon the entire group. At times certain members of the group may be in a different stage to others, which can cause the group as a whole to become unbalanced and with communication being compromised.

During this period agendas may be unclear and there may be differences in ways of working which can impact upon the individual in a negative way. There must be recognition and understanding of the limitations faced between stakeholders in the partnership. In a coordinated model where there are more than 2 agencies involved, the focus on clear and effective communication becomes ever more important. To keep the focal point on a beneficial outcome for individuals teams should:

- Play to each others strengths .

- Improve interaction by the use of a common language which is uncomplicated and clearly defined.

- Feedback to other members regarding shared approaches continually.

- Remain centred on promoting autonomous decision making for individuals.

- Not be overly agenda focused.

- Service user involvement paramount

Working in coordinated teams with individuals, allows information to be shared faster and identifies gaps in provision more effectively.

The Unified Model

A Unified Model: with amalgamated management, training and staffing structures for its services, which may be delivered by different sectors but are closely united in their operation (Tony Bertram, n.d.).

A unified model allows for multiple members of a partnership to be amalgamated, perhaps with the same management and staffing structures, but still having separate expertise from each other. An example of this is “Co-location”. Professionals such as occupational therapists, social workers, nursing and mental health team all work from the same place in collaboration. There are many benefits to this approach:

- Stakeholders see each other frequently and not just at reviews

- Less opportunity to miss important factors

- Information is likely to be shared immediately and more easily

- Communication is more effective

- Better team relationships

- Team members know each others roles and responsibilities more clearly

In Ruth Hardys article titled “How can social care and healthcare integrate together?”, Rob Greig, executive for the National Development Team for Inclusion spoke about good practice for integration:

(1) Co-location. People work better together when they are working alongside one another. (2) Open and public accountability back to the people using services. It’s a lot easier to justify decisions that are primarily about the interests of your own organisation, rather than the whole service system, and person using services if you are taking them behind the closed doors of your own internal management systems.” (Ruth Hardy, 2015)

With colleagues who are involved with individuals working at a common location, the probability of all members knowing each others limitations is high. There is also a somewhat less formal aspect to the working relationship, members will see each other regularly and have established relationships, and already be working effectively as a team. The possibility of the partnership becoming less professional is safeguarded through each particular agencies terms/codes of practice and conduct, and through legislation such as the Data Protection Act 1998.

The Coalition Model

A Coalition Model: where management, training and staffing structures of the services work in a federated partnership. There is an association and alliance of the various elements but they operate discretely (Tony Bertram, n.d.).

Similar to a “lead body” model in that it is a collaboration between autonomous organisations and does not have its own legal identity. It is likely to be a fixed-term arrangement. The key difference is that all of the partners are signatories to the grant or contract and the funds involved are allocated and distributed to the individual partners, who control their element of the contract and take legal responsibility for it (Collaborative working and partnerships, 2017).

A coalition is a collaboration between two or more independent organisations. This may be a temporary measure for the purpose of combining services for a limited period of time.

Benefits:

- Resource base is widened.

- Advice and services provided by professional bodies which are independent from the organisation delivering support resulting in unbiased and impartial provision.

- Problems identified more effectively.

- Wider range of choice and autonomy for the individual

- Each team has their own specific funding assigned, therefore the actions of other stakeholders do not affect individual assets.

- More cost effective.

- Additional choice for the individual.

- Clearly defined objectives

- Clarity of professional accountability

With each team having individual finances there are greater opportunities for the individual to have care and support tailored in their preferred way, and minimal scope for wasted resources. With less focus on the “budget” there is improved team cohesion and more opportunity for professionals involved to think outside of the box in terms of provision for the person receiving support. Ideally this should result in a wider range of choice and independence for the individual.

Conversely, a coalition model could be less appealing for the authority monitoring the distribution of funds due to the extra work load of incorporating numerous, smaller contracts. There is also a possibility of poor unity between partners who have limited experience or knowledge surrounding the roles of other members. This has the potential to impact negatively on the individual and on any outcomes. Autonomy can be so easily compromised if teams do not work together effectively, especially in individuals with learning disability or dementia where misunderstanding surrounding mental capacity can occur. It remains vital that collaborating agencies continue to work in agreed ways, adhering to local policy and codes of practice, and following national legislation such as The Mental Capacity Act 2005, The Human Rights Act 1998 and The Equality Act 2010.

What is Autonomy?

I want to talk a little about autonomy and its meaning within a health and social care capacity. How can we successfully ensure any individuals we support are exercising their independence and choice? Haralambos and Holborn (2013) describe autonomy as the following:

“That which concerns freely deciding upon and defining the goals, and planning how to achieve these goals”.

Autonomy is simply being self-sufficient, exercising choice, developing plans and having the freedom to do so respected without interference.

Hockey and James (1993), who authored “Growing up and Growing Old: Ageing and Dependency in the Life Course” stated that

“Personhood or being accepted as an individual who is a full member of society with rights – depends upon being accepted as an adult. Adults are autonomous and able to exercise rights and are responsible for their own actions. Other groups such as those with learning disabilities are often not seen as having Personhood with the ability to make choices or take responsibility”.

For those who receive support in a health or social care setting, and especially with individuals who have a learning disability, choice and independence can sometimes be overlooked. Carers or family may feel that the individual does not know what they want, and that because of their disability, dementia or age the choices they make cannot possibly make sense. It may be felt that doing something independently is too risky, or confusion within a team over who is responsible for making that decision. In short – there are many flawed excuses which prevent choice and independence being achieved but making it work isn’t rocket science. To maximise the autonomy of an individual with learning disabilities, it is vital that communication with them is maintained through their chosen method, and that the organisation is flexible with support , this increases the potential of making independent decisions

Ways to promote autonomy:

- Communicate effectively – Understanding and listening to what the client wants is fundamental to them achieving a good delivery of care. Document accurately and legibly, passing important information on to colleagues, managers and family members (this could be relating to medication changes, health, concerns, or support). It means being clear & articulate and ensuring anything you say or record is understood by others and that you also have a correct understanding of what is being said to you. Effective communication ensures that fewer mistakes are made, and that everybody has a firm understanding about the individual and their support.

- Assess and practice in a person-centred way – Acknowledge that the person receiving care is central to decision making and create a plan of support that takes this into account, while making it achievable. This incorporates everything about the person – what they want support with, who provides that support, the values they hold, food choices, personal appearance, health, social & leisure time, relationships, personal care and hygiene, plans for end of life, who looks after their finances and how they like to spend their day. Recognise that people who have their choices heard and acted upon have more control over their lives which ultimately leads to greater satisfaction with support, less stress and improved health and well-being.

- Work in partnership with the individual and their family – Agencies involved with the individual work as a united team to promote and deliver the best outcome possible whilst incorporating the clients choices and values. Different specialisms such as social workers, Drs, nurses, mental health teams and the care organisation collaborate and ensure each know what they are responsible for. In practice this can happen as part of a review, or in a multidisciplinary setting. Maintaining good relationships with families is an important part of good collaboration as it builds confidence in services and again ensures that the individual is the key figure within the team.

- Adhere to legislation, codes of conduct and policies/procedures – Having an understanding of legislation and policies and procedures which relate to the individual and to the job role can promote autonomy. Embedding this into everyday support ensures that as a care or support worker you are automatically applying that knowledge as second nature. Staff who have an understanding of appropriate legislation (Mental Capacity Act 2005 / Care Act 2014/Human Rights Act 1998) will recognise the positive effect that risk assessment can have on the independence of individuals, and will know to always assume that a client has the capacity to make a decision and to understand the consequences (unless a mental capacity assessment proves otherwise). They will challenge to guarantee the individual gets the chance to exercise their rights. Automatically incorporating data protection and safeguarding policies and procedures into care on a continual basis supports in protecting the client, and widens the scope for opportunities, decision making and control.

SUCCESSFUL PARTNERSHIP WORKING

The models of partnership establish that working in a collaboration can be extremely effective with multiple benefits to individuals IF (and only if!) it is done well.

How do we know that the partnership has been successful

- The personal choices and preferences of the individual have been achieved

- There is clear evidence that outcomes are of value to the individual – for example health, lifestyle and wellbeing improvements.

- Problems have been overcome

- Positive feedback is given.

- Family members are happy

- The numerous organisations involved feel they all worked well together, were respected and that they learned something about the roles of other professionals.

These achievements are often over shadowed by accounts of substandard care and support which can and do emerge through poor collaboration. The heart-breaking stories of Baby P and Winterbourne View showed the nation the atrocity of what can happen if teams that work in partnership “breakdown”. When partnership working goes wrong, it is usually the communication aspect that is the cause of the breakdown , with the result being the team failing to work effectively . When this does occur, critical information is missed, and there is the high probability of gross error in the care of the individual, abuse and even death.

In the case of Baby P, it becomes clear that there was a localised structure of “Buck-Passing” within services. Nobody wanted to be accountable for the oversight of such a horrific crime that had been missed for so long. How did the communication between police, doctors, schools, social services and the family break down so badly? How did it get to the point where the abuse of a child was so severe it caused his death, and was missed by every professional involved? Who takes the blame? Social service departments are stretched to capacity but expected to maintain safe practice without being subsidised for it.

“A British Association of Social Workers (BASW) survey of over 1,000 social workers published in May 2012 revealed enormous challenges facing the profession. Too many social work respondents to the poll indicated they were being stretched to breaking point, with 77% reporting unmanageable caseloads as demand for services escalates” (British Association of Social Work, 2013).

“The issue of funding is never far from any debate about the capacity of social workers to safeguard children and adults. Financial pressures were a constant refrain from those giving evidence, with frequent assertions that professionals are being asked, in effect, to practise in unsafe conditions – unsafe for social workers whose careers might be on the line should a tragedy occur but, above all, unsafe for the children at risk of harm” (British Association of Social Workers, 2013).

The Inquiry into the State of Social Work report details the ever increasing pressures on social service departments and how cuts to funding impact on protective services. In the case of Baby P, many professionals were involved and should have been efficiently collaborating and working towards a common goal with the safety of the child being paramount. But how is this expected to happen with departments spreading themselves so thinly? While ultimately blame for Baby P’s death must lay with his abusive mother, stepfather and uncle, had the combined failures of the professionals involved been discovered earlier, the childs death could have been prevented.

What is legislation?

The process of making or enacting laws (English Oxford Living Dictionaries, 2017).

Legislation (or “statutory law”) is law which has been produce by a governing body in order to regulate, to authorise, to sanction, to grant, to declare or to restrict. In terms of events, Legislation defines the governing legal principles outlining the responsibilities of event organisers, and other stakeholders such as the local authority, to protect the safety of the public (London Events Toolkit, 2012).

All organisations working in the context of health and social care must incorporate National legislation into their practice and provide their own guidelines (called policies and procedures) which translate laws such as the Care Act 2014, into clear and definitive strategies relevant to that agency and the client base they support.

Policy – A set of ideas or a plan of what to do in particular situations that has been agreed to officially by a group of people, a business organisation, a government or a political party (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Procedures – A set of actions that is the official or accepted way of doing something (Cambridge University Press, 2017).

Current Legislation and practice relating to health and social care

Valuing People – A new strategy for learning disability for the 21st Century. Objective 11 partnership working to promote holistic services for people with learning disabilities through the use of effective partnership working between all relevant local agencies in the commissioning and delivery of services (Department of Health, 2001).

The Department of Health’s “Valuing People Now” 2001 Command Paper specifically focuses on those with learning disabilities, and outlined to the government how to improve services by issuing guidance to all learning disability partnership boards. Within Objective 11 The Department of Health highlighted that agencies should be working together in collaboration to provide a holistic service for individuals. For those individuals that have a learning disability it means that local authorities now have a clearly defined duty to provide an assessment and meet needs. The guidance in “Valuing People Now” has had an impact, especially in recent years with the media showing how badly care can go wrong without good team work. The influence of the guidance can be seen in local equal opportunity and diversity policies and has led to increased understanding of how disability can affect an individual.

- The concept of diversity encompasses acceptance and respect. It means understanding that each individual is unique, and recognising individual differences as well as the things we have in common. These differences can be along the dimensions of disability, race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, gender reassignment, socio-economic status, age, physical abilities, religious beliefs, political beliefs or other ideologies” (Greenwich Mencap, 2011).

- Equal opportunities means to treat someone with fairness irrespective of race, ethnicity, disability, gender, sexual orientation, gender reassignment, socio-economic status, age, physical abilities, religious beliefs, political beliefs or other ideologies.

- Managing equal opportunities means that practices are put into place and monitored to make sure people are not treated unfairly. This applies to all our working conditions, polices, procedures and the way people and their families are supported” (Greenwich Mencap, 2011).

It has become more apparent that there is a crucial requirement to work in in partnership alongside those with intellectual difficulties and their families to safeguard from abuse and ensure maximum independence and inclusion. To continue to remain appropriate the command paper needs to regularly review its relevancy (i.e ensure words used to describe learning disability are still current and socially acceptable, include feedback from those receiving services) and ensure it is reaching the maximum target audience.

The Care Act 2014 includes a statutory requirement for local authorities to collaborate, cooperate and integrate with other public health authorities, for example, health and housing. It also requires seamless transitions for adolescents moving into adult social care services (Department of Health, 2014).

The act acknowledged that improvement was needed in partnership working, and provided guidance on how and when services should be collaborating. There was also recognition that there were too many current laws surrounding how care should be delivered, which had led to services, families and Local Authorities becoming confused about how to correctly implement that support. The Care Act 2014 clarified this, which meant that authorities and agencies were able to now work with improved understanding of their own roles, and how to deliver this to individuals while incorporating the principles of well being.

Under the Care Act 2014 there is also provision made for unpaid carers – most vulnerable individuals are looked after by family members and this can mean people who care for their loved ones can quickly find themselves isolated, excluded and suffering from “burn out”. This provision reinforces the aspect of “collaboration” as the act not only recognises previous flaws in team-working, it now acknowledges the wider implications that caring can have on the family unit. The Care Act also changed the criteria for having needs assessed. Individuals are no longer assessed based on how at risk they are, but on their ability to achieve their chosen desired outcomes.

This legislation effectively considers “autonomy” to be a critical element of well-being and outlines how and why integrated ways of working are integral to getting a good delivery of care.

“Desired outcomes (of the individual): these are the outcomes a person wishes to achieve in order to lead their day-to-day life in a way that maintains or improves their wellbeing. They will vary from one person to another because each individual will have different interests, relationships, demands and circumstances within their own life. These are the outcomes that the assessment should focus on” (Social Care Institute for Excellence, 2015).

“Local authorities must carry out their care and support responsibilities with the aim of joining-up the services provided or other actions taken with those provided by the NHS and other health-related services (for example, housing or leisure services). This general requirement applies to all the local authority’s care and support functions for adults with needs for care and support and carers, including in relation to preventing needs” (Department of Health, 2014).

Chapter 15.1. ” For people to receive high quality health and care and support, local organisations need to work in a more joined-up way, to eliminate the disjointed care that is a source of frustration to people and staff, and which often results in poor care, with a negative impact on health and wellbeing. The vision is for integrated care and support that is person-centred, tailored to the needs

and preferences of those needing care and support, carers and families” (Department of Health, 2014).

In practice the Care Act 2014 can be incorporated into the care and support of individuals by adhering to Duty of Care and safeguarding policies and to the Codes of conduct for Social Care workers. To further improve implementing the legislation with a view to choice and a more holistic collaboration, Local authorities should draw on feedback more regularly about the type of accommodation vulnerable adults want to live in and bring this specific requirement in line with the current population of individuals who are at risk. This will require housing associations and local authorities to integrate better and be absolutely transparent to the public about what is available, while still recognising what needs to be available.

The Health and Social Care Act 2012 promotes joint working and outlines how authorities along with their partner commissioning groups must consider the extent to which needs could be more effectively met. The act places the onus on local authorities to prepare “joint Health and Well-being Strategies” which must outline the provision of health and social care services in the area, and detail how the two can be more closely integrated. In particular, CCGs and HWBs have specific duties to promote integration and to consider the use of integrative tools available under Section 75 of the NHS Act 2006 (Heath, 2014).

To further promote partnership working there should be a streamlining of groups both nationally and locally, and a distinct clarification of who is responsible for what. With so many boards and groups evidently under the same umbrella it may become confusing within a collaboration, especially for the individual. There is also the risk of duplicating work through lack of clarity, which means outcomes for the individual could be slowed down.

“No Secrets” was incorporated by the Care Act in 2015. It provided a code of practice for the protection of vulnerable adults and promoted partnership working between commissioners and providers of health and social care services. It was successful because it brought together a large number of stakeholders – including the police, the NHS Confederation, Association of Directors of Social Services and key voluntary organisations (Bonnerjea, L. 2008).

“No Secrets” detailed how there should be collaboration with the public, voluntary and private sectors and how service users, their carers and representative groups should be consulted. Local authority social services departments should co-ordinate the development of policies and procedures (Department of Health, 2015). The guidance had clear definition of how to achieve effective collaborative working and recognised the necessity of having transparent lines of accountability. Part of the “No Secrets” guidance aimed to balance the requirements of confidentiality with the consideration that, to protect vulnerable adults, it may be necessary to share information on a ‘need-to-know basis’ (Department of Health, 2015). This is incorporated into local Confidentiality and Safeguarding policies and adhered to, but its application can be a cause of conflict within a partnership.

Individuals, especially those with a learning disability whose understanding may be impacted, can feel that they have been slighted or let down if information they consider private has to be shared to keep them safe. The collaboration can also become unbalanced if other stakeholders are unnecessarily withholding information about the individual through misuse of power or through inappropriate attachment to their client.

There is a clear need for a sound understanding and knowledge of the confidentiality surrounding safeguarding adults. Often members of the public have a sense of shame and anxiety about passing on information which they consider to be no business of theirs. To eliminate this it would be beneficial to introduce this subject not only to those who work in the remit of health and social care, but also into schools and colleges and through the use of TV and social media with a view to encouraging people to “speak up”.

Another potential hazard in replacing No Secrets, is that this “standalone guidance” may somehow have been buried amid the huge Care Act 2014 and that previously as a specific document its main points and the message it was giving were easier to apply and understand.

How differences in working practices and policies can affect collaborative working

Despite the best intentions, conflict can arise within the partnership relationship. Gaps between theory and practice can arise if the researchers developing legislation are unrealistic or place demands upon health and social care professionals which simply cannot be achieved. There is a possibility of the differing geographical areas of stakeholders posing problems within the team. Agencies may be operating in more than one county, each county having its own statutory responsibilities and priorities. Policies can also become out of date extremely fast as new studies and investigations demonstrate more effective ways of practice.

White and Dudley-Brown (2012) suggest this could arise because of a lack of personal contact between research and policy makers, poor quality of research or through having a high turnover of policy-making staff. They also proposed the cause could be due to:

- Power and budget struggles

- Lack of timeliness or relevance of research

- Mutual mistrust, including perceived political naivety of researchers and scientific naivety of policy makers

In order to rectify this they recommend:

- time-scaled and good quality research

- personal contact between researchers and policy makers

- Inclusion of research that the community or clients have asked for

- Research that included a summary with clear recommendations

If decisions makers are competing with each other over which strategies are placed into legislation, the result can be a fragmented and unworkable document which instead of being defined and transparent may be open to vague interpretation. There is also the possibility of individual decision makers each holding a different view of what is crucial and what is not. The outcome can mean there is a huge disparity between what is expected and what is actually delivered in practice. The effect of this in a working partnership relationship can be damaging and multifaceted:

- Resentment surrounding what can be delivered with unrealistic budgets

- A feeling of clear divide between policy makers and individuals/front line staff

- Lack of satisfaction for the individual and the team

- High staff turnover/discontent within the job role

- Risk of local authorities unfairly measuring organisations by performance despite being held back by impractical policies

- Risk of poor care, abuse or neglect of the individual

If an organisation has a high staff turnover it poses risks for both the individual and the team. A trusting relationship with a strong knowledge of what the client needs cannot be formed if all members are persistently new and unknown to each other. An effective and continuous flow of care cannot be delivered if stakeholders are constantly having to reintroduce themselves and explain their role. This leads to duplication and wasted time and resources for all involved. Legislation and policy should remove barriers, not create them. Olivia O’Connel , an implementation officer in social services proposes that there is a wide gap between those who implement the policies and those who deliver the support and suggests that this can lead to:

“fear of exercising too much judgement discretion due to accountability”.

“Social Workers struggling with managerial aspects” (O’Connell, 2012).

Why does this occur?

This could result from unrealistic expectations of both management and of Social Work as a whole. With constant media reports about social workers being spread too thinly due to massive case loads, it becomes evident that the current law is not establishing how much is too much. Poor policies stemming from legislation made by researchers with little to no knowledge about the practicalities of the job role may result in social workers feeling unsure about making crucial decisions and hesitate because they may be solely accountable for their choices and the implications. The “Unsure” aspect demonstrates not only a gap between theory and practice, but also establishes the need for clearer guidelines in legislation, policy and codes of practice, and expectations which are representative of what can actually be delivered. Improvement can only come through a better staff support system for social work teams while incorporating transparent and definitive roles.

To effectively work as a team, each organisation must have practicable policies with roles which are clearly distinguishable from other members. If a single organisation within the partnership has an unproductive policy to which they are adhering, it will affect the quality of the care they provide, and ultimately the vulnerable client. Tension within a team-working context can arise if certain members have policies which are vague and unclear. For example timescales for outcomes may not be plainly specificied which can lead to other members of the team becoming resentful of the member who is essentially preventing the rest of the group from achieving outcomes, and putting the person being supported at risk.

Inequality between policy and practice is seen in all aspects of health and social care. The irony is that those who create the legislation and policies promoting the benefits of partnership-working, clearly are not working in partnership with those having to provide the front line support. Legislation/policy production should incorporate the realistic views and knowledge of those workers who are experienced in their field and should involve constant feedback as to whether it is workable.

Click here to go to Unit 1 – Communicating in Health and Social Care Organisations

Written by S.D , 2016